Commercial Hardscapes

Developed to Solve Every Challenge

Get the products you need to get the job done, and the expertise to get it done right.

Locally Made Since 1995

Explore Products

Get Every Detail, Every Step of the Way

Find the support you need. From identifying which products are best suited for your project to assembling engineered designs, we’re here for you at no additional cost.

Design

Create a better hardscape. From paver size to layering pattern, our team can help.

Site Planning

Maximize the value and versatility of your site with guidance from our experts.

Product Selection

Not sure which product will work best? We can help you figure that out.

At Your Service

Paving System Support

Walk or drive — create surfaces that can handle any type of traffic.

Stormwater Management Support

Match the onsite soil conditions, design storms and local regulatory requirements.

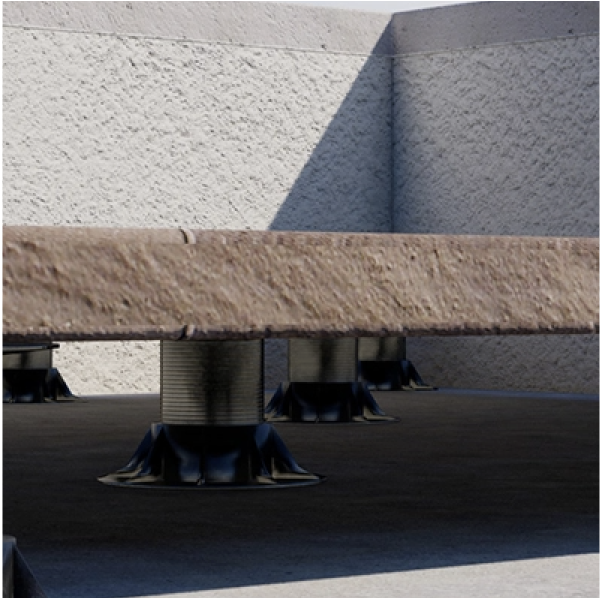

Rooftop Support

Elevate your plaza decks and rooftop terraces with a wide range of support services.

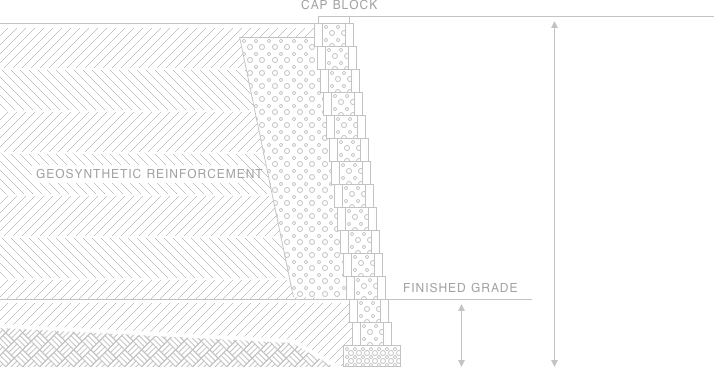

Retaining Wall Support

Stay on budget with planning help from our Design and Engineering teams.

Want to See Our Products in Action?

Featured Case Study

Whole Foods Marketplace